An Unexpected Lesson from the Classroom on Explosion Safety

When you see an explosion happen, you become incredibly attuned to the importance of safety. I unexpectedly got this lesson back in 1982, in Mr. Strong’s 8th-grade classroom, when a science experiment went wildly wrong.

One of my friends, Scotty, was demonstrating the importance of not using flames on a production floor in a dusty environment. His setup included a bowl of coffee-mate powder and a candle inside a large box, with a straw coming out the side of the box. With the straw, he could blow into the box to create the dust storm, which should ignite. However, after blowing multiple times through the straw, with no effect (who hasn’t had a demo fail in front of an audience?), he decided to put his head over the box and blow down directly into the bowl to create the dust storm.

The next thing we knew, Scotty’s head was fully enveloped in flames as the candle caused the dust to spontaneously combust straight up out of the box, looking to all of us like his head was blown off. Fortunately, besides badly singeing his eyebrows and hair, he walked away uninjured, and my classmates and I were able to laugh at the memory.

The Importance of Intrinsically Safe

Unfortunately, when a dust explosion happens in real life, it is no laughing matter. The same phenomenon that can be demonstrated in an 8th-grade science class can also cause a life-threatening disaster. In 2008, the Georgia Imperial Sugar refinery suffered a blast due to a similar dust explosion, but on a much larger scale. And between 2020 and 2024, Dust Science Safety recorded 215 dust explosions worldwide.

To prevent these incidents, the industry developed a standard called intrinsic safety, or IS, which allows electronics to be certified to operate in hazardous environments. Many of our customers’ sites are at risk due to volatile gases or dust, making intrinsically safe (IS) equipment a must for operation in these areas. But in every case, we have to dig into the specifics of IS to understand the level required and the standards that the customer needs to follow.

In this blog, we’ll dig into intrinsic safety topics to help you better understand the basics of hazardous environments and devices that can operate there:

- What Does “Intrinsically Safe” Mean?

- What Makes an Environment Hazardous?

- Intrinsic Safety Classifications

- What Standards Govern Intrinsically Safe Devices?

- Who Certifies Intrinsically Safe Devices?

- How do you know if you need intrinsically safe (IS) devices?

What Does “Intrinsically Safe” Mean?

Intrinsic safety is a protection method that limits a device’s electrical and thermal energy to prevent ignition and explosion. A device is considered “intrinsically safe” if it is certified to be used safely in a “hazardous environment”. These devices undergo rigorous testing, following a set of safety standards. Different organizations worldwide certify and label equipment in slightly different ways, but the core goal remains the same. Ensure the safety of people working in hazardous environments.

What Makes an Environment Hazardous?

Any workplace where combustible substances may be present is referred to as a “hazardous environment”. Some common examples include:

- Underground mines: Methane or coal dust can create highly explosive atmospheres.

- Oil and gas plants: Flammable vapors from fuel or chemicals can easily ignite.

- Grain, flour, or agricultural processing plants: Fine organic dust particles, like flour, sugar, or grain dust, are highly combustible when suspended in air.

- Manufacturing facilities: Chemical vapors, fibers, or powders from production processes all pose an ignition risk.

Essentially, a hazardous environment is any place where you wouldn’t want to light a match. These volatile atmospheres make it imperative that electronic devices in operation cannot cause even the tiniest of sparks. Understanding the hazards is the first step in choosing the correct equipment to ensure safety.

Do ‘explosion proof’ and ‘intrinsically safe’ mean the same thing?

The symbol Ex shown here can be found on ATEX-certified electrical equipment, meaning it can be used safely in explosive atmospheres. When thinking of this level of safety, it’s natural to assume that equipment with this label is “explosion-proof”.

However, there are different levels of Ex certification. The specific Ex-d certification is often referred to as “explosion proof,” but even this is incorrect. Ex-d certified equipment is “flame proof,” meaning that a flame or spark cannot escape the housing, even in case of an explosion. Equipment with this certification is often bulkier and harder to install.

It may not meet Michael Bay’s standards for explosions in Transformers, but this video demonstrates the testing procedure for explosion-proof equipment.

It may not meet Michael Bay’s standards for explosions in Transformers, but this video demonstrates the testing procedure for explosion-proof equipment.

While the IS and Ex-d standards are in alignment with each other, they actually do not overlap. Most Intrinsically Safe certified devices are not “explosion proof” because they are not built to contain an explosion. IS simply means the device or equipment is built to avoid ignition altogether by limiting its thermal and electrical energy.

Intrinsic Safety Classifications

Hazardous environments where IS equipment might be used are classified by Classes, Groups, Divisions, and Zones.

- The type of hazardous material present.

- The likelihood and duration of the materials being present.

The naming conventions and categorizations differ based on the international standard. We will define the basic terms used to define intrinsic safety.

The type of hazard: Classes and Groups

North America uses Classes and Groups to define the general type of substances that are present in the environment:

- Class I – Flammable gases and vapor fumes

- Group A – Acetylene and similar

- Group B – Hydrogen and similar

- Group C – Ethylene and similar

- Group D – Propane, Gasoline, and similar

- Class II – Combustible dust

- Group E – Conductive (powdered metals)

- Group F – Combustible carbon dust (coal, coke, etc.)

- Group G – Grain dust.

- Class III – Ignitable fibers or debris (e.g., textile mills, woodworking facilities)

For example, the presence of propane would be labeled in North America as “Class I, Group D”.

Internationally, equipment Groups are used to define the application sector. E2S provides a comprehensive table of different codes for each type of gas and dust in both North America and Europe (ATEX).

- Group I – Mining environments

- Group II – Non-mining gas atmospheres

-

-

- IIA – Propane

- IIB – Ethylene

- IIB – Hydrogen

- IIC – Acetylene

-

- Group III – Non-mining dust atmospheres

-

- IIIA – Combustible fibers

- IIIC – Conductive dust

- IIIB – Non-conductive dust

This guide from E2S provides a comprehensive table of different codes for each type of gas and dust in both North America and Europe (ATEX).

The likelihood of the hazard: Divisions and Zones

North American standards use Divisions, where a hazard is or is not present:

- Div. 1 – Hazardous conditions MAY be present under normal conditions.

- Div. 2 – Hazardous conditions are NOT likely present in normal operations.

International standards use Zones, but break down the type and likelihood of the risk:

Explosive Gas Atmospheres

- Zone 0 – Continuous or Frequently Present Risks

- Zone 1 – Risks Likely to Occur in Normal Operation

- Zone 2 – Risks Rare and Short-term

Combustible Dust Atmospheres

- Zone 20 – Continuous or Frequently Present Risks

- Zone 21 – Risks Likely to Occur in Normal Operation

- Zone 21 – Risks Rare and Short-term

Putting It Together

In North America, an area where propane gas may be present during normal operations would be classified as Class I Div 1 Group D. The European equivalent for this same environment would be Group II, Zone 1, Gas Group IIA. This poster from the CSA Group brings all these terms together at a high level.

What Standards Govern Intrinsically Safe Devices?

Devices can’t simply claim to be intrinsically safe; they must be tested and certified by accredited labs. These agencies ensure the equipment meets international safety standards for hazardous environments.

The following standards are used around the world to govern Intrinsically Safe devices:

- IECEx: The international standard for safe use of equipment in explosive environments, developed by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC).

- ATEX: This standard is developed by the European Commission and stands for ATmosphères EXplosibles. It is enforced by law for any IS equipment sold in the European Union.

- NEC/NFPC 70, Article 504: This is a part of the National Electrical Code (NEC) developed by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), broadly used for electrical equipment used in the U.S. and parts of Canada.

- Part 18 of the CEC: The Canadian Electrical Code, a safety standard maintained by the CSA group, is used for all electrical work and equipment in Canada.

ATEX and IECEx technically align very closely, with only a few exceptions (source).

Who Certifies Intrinsically Safe Devices?

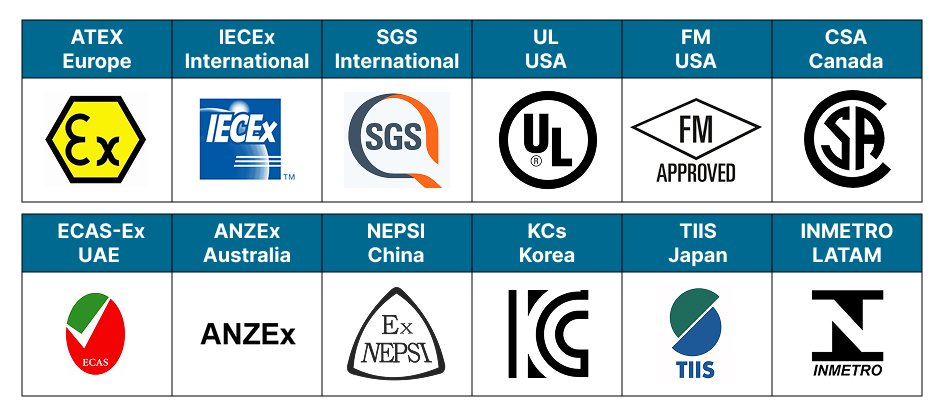

Common certifying bodies that test equipment based on standards in the United States are called nationally recognized testing laboratories (NRTLs). These NRTL labs and others can also certify internationally. A limited selection includes:

- Underwriters Laboratories (UL): US-based and both a standard-writing body and a certification/testing organization for North America. Certifies to UL standards, CSA, and IECEx.

- CSA Group: Originally the Canadian Standards Association, the CSA group changed its name to reflect its broader capabilities of writing standards, testing, inspection, and certification of electrical equipment, including Canadian and IECEx standards.

- FM Global (Factory Mutual): A standards development organization and testing lab for explosion-proof and intrinsically safe devices.

- SGS (Société Générale de Surveillance): A Swiss-based, multinational company that tests equipment to ATEX and IECEx standards.

You will often find one or a combination of these logos on intrinsically safe equipment. Each must go through a different approval process to be certified. Markings on the equipment will specify the type of environment the product has been tested to be safe to use in and the certifying body.

How do you know if you need intrinsically safe (IS) devices?

In summary, any work environment that contains flammable substances that could ignite under normal operating conditions requires intrinsically safe (IS) devices. Based on the country you are in, there are different agencies for each step in the Intrinsically Safe process. Specifically, in the United States, this is the chain:

- The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) code sets the guidelines for adhering to intrinsic safety in your workplace.

- OSHA, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, enforces safety regulations nationally. Each state might have an additional governing body, such as Cal/OSHA in California, which enforces higher regulations.

- Nationally recognized testing laboratories (NRTLs) certify products to confirm that they meet the required intrinsic safety standards before they can be used in hazardous environments.

But even in workplaces where Intrinsic Safety is required for some areas, there is nuance that needs to be understood. In the following two blogs, we will cover:

- Do you actually need IS for your use with emergency mustering or identification? (coming soon)

- If Intrinsically Safe devices are required, what options do you really have? (coming soon)