This blog covers three different card types: ID Prox cards, memory storage cards, and microprocessor cards (smartcards). Click here to jump to the write-up of use cases, benefits, and disadvantages of each. Read on to learn more about Telaeris’ start in credential technology.

(GO) CARD Memories

At Telaeris, reading security badges from a handheld device is our business. Thanks to decades of experience and partnerships with industry leaders, including Elatec, HID, Farpointe, and others, we support more access control badges than any other reader. From the outside, all these badges seem to operate the same – present the card and see the red or green LED indicating success. However, the underlying technology of ID-only badges, memory cards, and microprocessor (μP) cards are VERY different. It is worthwhile to understand the differences between these technologies.

When I first started working with RFID smartcards at my previous company in 1995, I had zero idea of this difference. Cubic’s (actually Cubic Automated Revenue Collections Group, fondly known as CARCG) customers had a desire for an RFID card for transit payment. As a jack-of-all-trades, I stumbled into working as part of the 5-man R&D team tasked with creating this product, named the GO CARD. We were given a number of goals for this product:

- Sufficient memory to store a purse or transit pass

- Cryptographically secure access to read and write data

- Authenticated communication

- Operate in under 200ms, to keep commuter lines moving

Little did I realize that understanding the ins and outs of RFID, cards, identification, security, authentication, cryptography, and chip specification would end up defining a large portion of the next 30 years of my life and, to a significant extent, Telaeris as a company. The requirements that drive the choice between ID, memory, or microprocessor cards can be subtle, but for those who care about security and functionality, it is important to understand.

Overview of card types: ID, Memory, and Microprocessor

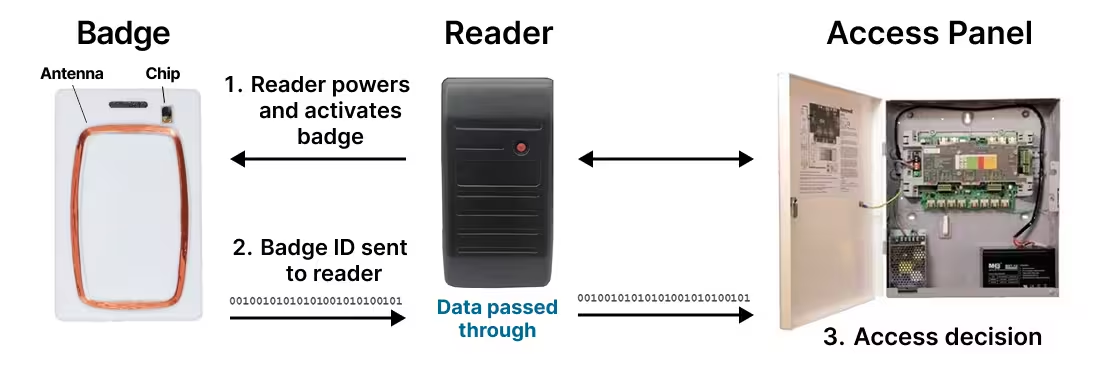

The first security badges were ID-only proximity cards. These ID cards simply transmit a unique identification number (UID) to a card reader.

Memory cards or smartcards are a significant technical step above ID cards. Like ID proximity cards, memory cards have UIDs, called Card Serial Numbers (CSNs). However, these cards can also store data, ranging from a couple of bytes to megabytes of information.

Microprocessor smartcards also have memory, but the chip used in the card can be programmed only to run specific applications to perform desired tasks.

Each of these cards has been used for access control. From a user standpoint, the operation of all three seems to be the same. Users will often call them proximity/Prox cards or smartcards. These all use an inductively powered chip which receives energy from the reader.

We’ll mainly discuss these cards in relation to access control, but we’ll also touch on other use cases for each. Let’s dive a little further.

ID (Prox) Cards for Access Control

ID-only or Prox badges have been unlocking doors since the 1970s, but 125KHz Prox cards that we still use first came on the scene in the 1980s. The only information contained in these badges is their ID number, often just a 26-bit Wiegand number. Determining if a card is valid happens at the access control panel.

The operation for Prox cards is simple. When the reader powers the badge, the badge number is sent in the open RF field. When Prox badges were introduced, the security of these badges was determined by:

- The difficulty of construction

- The choice of RF modulation (ASK, PSK, FSK)

- The bit format of the data

Unfortunately, Prox cards today are generally easily clonable. Common types of Prox badges found in access control include:

- Casi-Rusco

- EM

- FarPointe

- HID Prox

- Indala

- Securakey

The main disadvantage is that most Prox cards have limited security, making them easy to clone. Casi-Rusco and some HID Prox badges obfuscate their data with a proprietary “secret sauce” for their bit formats. Farpointe, Indala, and Securakey provide an extra layer of security, where the card is encoded to be read only by readers with specific keys.

These were the first type of cards used widely for access control. For close to 2 decades, they were the standard in the industry. Because of this, 40 years after they were introduced, many facilities still use legacy Prox cards in their access control systems.

Memory Cards (13.56 MHz Cards)

Memory cards primarily came into existence to meet the requirements of public transportation. Metro systems had to move riders quickly through turnstiles to reduce congestion. For every card transaction, they needed to read the stored value, calculate the fare, and write the new value back to the card, fast enough not to slow down the queue.

While there would be other uses for memory card technology, a market like transit with millions of cards and new cards constantly being purchased drove the wide adoption of this technology.

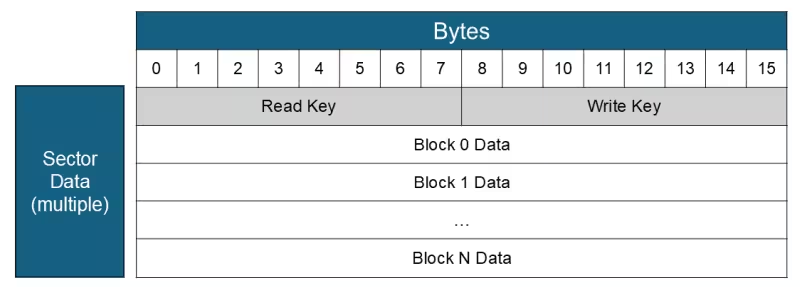

From a high level, memory cards are built to store data, secured with separate keys to read and write data. These cards also have a static CSN, similar to Prox badges. Another feature is the ability to support separate “applications” by having specific memory sectors secured by different keys. A high-level diagram of a memory card sector is shown below.

In the late 1990s, memory cards first started to be used for access control. Back to my experience at Cubic, in 2000 we enabled an agency in Chicago to have a dual application badge for employee access control and a pass for the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA). We built an access control reader which used one sector of the GO CARD memory for employee data and separately had the CTA sector encoded to support metro usage. While cards today continue to have the ability to have separate sectors to support other application data, these are infrequently used.

When using memory cards for access control, there are many ways that can make the system almost as insecure as simple ID Badges described in the previous section. These include:

- Using the CSN for the access control number: chips exist that allow hackers to set the CSN of a cloned card which would allow an attacker inside your facility.

- Using old chip technology: In 2007, the MIFARE Crypto1 was hacked, allowing hackers access to read and write data on cards.

- Using static read/write keys: Exposing a single card key in any way (Brute force attack, Social engineering, etc.) makes all cards vulnerable to hackers.

- Putting card keys in applications that might be decompiled.

- Using old standards: Old encryption/authentication/random number standards provide entry points for hackers who love to decode these sorts of challenges.

Some good practices we have seen for securing memory cards include:

- Current Standards: 3DES and AES are generally well regarded.

- Diversified Keys: Each card has unique keys determined by a master key and algorithm connected to the card CSN. NXP provides a public standard AN10922 that has been vetted for this.

- Using Security Access Modules (SAMs): SAMs are tamper-resistant cryptographic coprocessors that allow keys to be stored and used securely.

Today, many access control cards are memory card based, including badges from HID, STid, Legic, and Allegion. These cards are based on the ISO14443 and ISO15693 standards, the majority of which use NXP’s Mifare product line.

Products from Infineon, TI, Sony, as well as Mifare knock-off products can also be found, often having strong footholds in specific countries or regions.

Microprocessor (μP) Smartcards

In 1980, Intel released the 8-Bit 8051 microcontroller for embedded devices. Today, the 8051 is at the heart of NXP’s DESFire, likely the most popular microprocessor smartcard product line. Microprocessor smart cards use an on-card operating system (COS) to run applications and actively manage and control access to memory blocks. This latter functionality builds on the utility of memory cards, but unlike memory cards, file sizes can be adjusted per application. But beyond this, they can run applications that use data in memory, without exposing the data itself.

Going back to the last section, a transit memory card simply stores the purse value. The reader performs all the operations: reading the balance, deducting the appropriate fare, and writing the new balance back to the card’s memory. If an attacker learns the keys, they can use another device to effectively print themselves money. With a microprocessor card, two applications can be created to have a higher degree of security:

- Deduct fare application: Deploy at every gate with lower security

- Add fare application: Deploy at recharging kiosks with high security

Microprocessor smartcards are commonly used for things like financial payments and government credentials. Many countries in Europe and Asia use microprocessor smart cards as their citizens’ national ID cards. In the USA, the standard ID cards, PIV and CAC, used respectively for civilian and defense personnel identification are microprocessor-based. These cards hold not just identity information but also digital signatures, biometric data, and information for logical access.

Any facility that requires strong security features will find microprocessor smartcards ideal; they adhere to standard communication protocols and employ robust encryption algorithms to secure data and transactions. Some of these standards include:

Smart card standards:

- ISO/IEC 7816 – contact card standard

- ISO/IEC 14443 – contactless card standard

- EMV (Europay, Mastercard, and Visa) – global security protocol for chip-based payment cards

Encryption algorithms:

- Advanced Encryption Standard (AES)

- Triple Data Encryption Standard (3DES)

- RSA (Rivest-Shamir-Adleman)

- ECC (Elliptic Curve Cryptography)

In a conversation I had with Scott Lindley, General Manager at Farpointe Data, he anticipated that in the future all access control badges would be microprocessor-based, driven strongly by regulations starting in the EU and then percolating to the rest of the world. And as our industry moves to mobile credentials stored on your cell phone for access, these can be easily thought of as very heavy and thick microprocessor based badges.

Conclusion

The basic use-cases of Prox, memory card based, or microprocessor based badges seem the same from the user perspective. Present card, open door…or in the case of our handheld authenticator, view user image, name and permissions for validation. But under the hood, the newer cards provide significantly more security. With these, security officers can be assured that the badges used to get into the facility were issued by their office and have not been compromised.

But regardless of whether you are using Prox, memory, or microprocessor cards, the powerful reader at the heart of our XPressEntry devices can be delivered to securely read any of them for:

- Entry/Exit tracking for buses, temporary gates, or construction sites

- Identity verification at secure facilities

- Attendance and time tracking

- Emergency mustering

Our readers have also been built into tablets, kiosks (desktop and full-height), wall readers, and vehicle-mounted devices, making it the most flexible option for any scenario that requires employee identification or mustering. We list the technologies that our devices support on our website → https://telaeris.com/supported-card-types.

If you have any deep questions about badge technologies, our engineers are always available to help.